The Quiet Economy of Power: When Family Court Reinforces Financial Inequality

- Melanie Pelouze

- Oct 10, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Oct 22, 2025

By Melanie Pelouze

We know these stories from the movies, the ones who look harmless until the curtain lifts. Gaslight, Sleeping with the Enemy. Single White Female. Stories of charm, obsession, and control so outrageous we label them thrillers.

In real life, the plot is quieter. The control isn’t cinematic, it’s subtle, procedural, and hard to name until it’s already taken root. There are no climactic escapes, no final scenes. Sometimes, the story doesn’t end when you leave. Sometimes, it starts again, only this time, in family court.

The Quiet Work of Control

Before it became financial, it was psychological.

He never shouted. He didn’t leave marks you could photograph. Instead, it was precision work — subtle corrections, quiet critiques, the kind of put-downs that masquerade as concern.

“You’re remembering wrong.”

“You’re too sensitive.”

“Maybe you should get that checked out.”

After enough of these exchanges, I started to wonder if something was wrong with me. The gaslighting was so relentless that I actually scheduled an MRI to see if my brain was malfunctioning. That’s how effective covert manipulation can be, it makes you question your own cognition.

Researchers call this entrapment psychology: a “death by a thousand cuts” strategy that dismantles self-trust one comment at a time. By the time I left, I was a shell of my former self, still high-functioning, still working, but doubting every instinct. And that, I now understand, was the point. Because when someone loses control over your mind, they often find other ways to control your life.

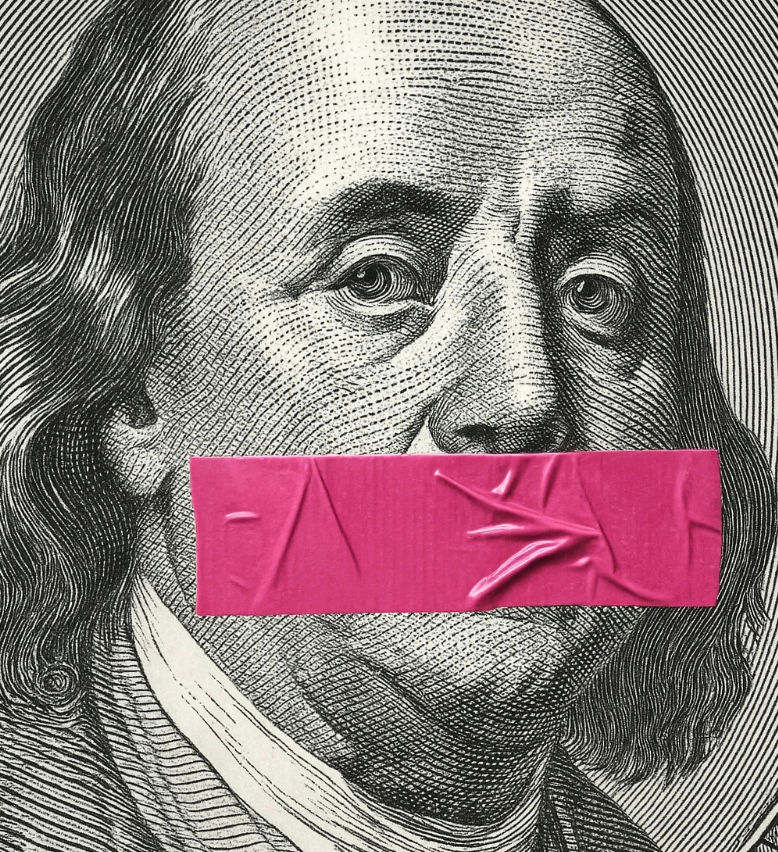

The Currency of Control

After I left, the control didn’t end, it simply changed shape.

At first, it showed up in small reversals, quiet redefinitions of everything we’d once agreed upon as parents. Psychologists call this counter-parenting, when cooperation is replaced by contradiction, and shared values become battlefields. We had raised our children to be thoughtful, spiritual but questioning, Unitarian, open-minded. Suddenly, they were being ushered into Catholic mass. We’d valued balance and unstructured time; now it was constant motion, over-scheduled weekends, exhaustion presented as virtue.

It was a campaign of quiet contradiction, the undoing of shared values, the rewriting of our family’s compass. Each reversal reminded me that cooperation was no longer possible, and that confusion itself had become the point. Our children felt it.

Gradually, that chaos found a new language: numbers.

What began as shifting values turned into shifting economics, every moral reversal mirrored by a financial one. Where we had once shared responsibility, I now carried the imbalance alone. The pattern didn’t vanish; it professionalized. During our marriage, he’d resisted every improvement; no new paint, no upgrades, no investment in the home we shared. Restraint was his rule, austerity his virtue.

After the divorce, that restraint evaporated.

What had once been frugality became display. Now, the control lives in a brand new, six bedroom, $1.5 million house. Professionally painted with 2 new cars in the epoxy-coated garage, pool tables and Ps5's, Italian espresso machines...even a new designer puppy.

That house was financed by a million-dollar family gift and... by me.

Every month, I pay $1,800 in court-ordered “support,” which means I must earn nearly $2,600 before taxes to subsidize him. For him, it arrives tax-free. On top of that: 63 percent of every extracurricular activity he enrolls our children in without my consent, plus orthodontics, copays, and incidentals. Some months, nearly $3,000 leaves my hands before I’ve paid for my mortgage or groceries.

I am a contract worker. No paid leave. No vacation. If I’m sick, I don’t get paid but I still pay him.

He gets four paid months off a year. He builds equity. I tread water. He gets rest. I work harder.

This is not support. It’s state-sanctioned financial control a postscript to the marriage, written in legalese. And it’s playing out every day, in thousands of courtrooms just like ours.

Spreadsheets as Weapons

I recently returned home from an eighty-hour week, fighting for the planet and our kids’ future. Instead of being met with something resembling kindness, I was met with not one, but two certified letters: nearly three hundred pages of spreadsheets, screenshots, and accusations.

Ten minutes late to a game? Documented.

Gave my daughter a phone? A violation.

Every detail catalogued. Every perceived imperfection preserved.

Researchers now call this legal systems abuse, when post-separation partners weaponize court procedures to continue control. In a 2019 study in Violence Against Women, Professors Heather Douglas and Julia Tolmie found that “some perpetrators exploit legal systems as tools of ongoing coercive control through repeated filings and documentation.”

What the court sees as paperwork, I see for what it is: obsession disguised as diligence.

The Bias in a Buttoned Shirt

The person doing this isn’t unemployed. He’s a professional in the counseling and education field, trained, credentialed, articulate.

He walks into court, a therapist office or mediation; calm, polite, pressed, and prepared. And the systems bends toward his Ph.D.

Researchers have called this the credibility discount a bias that rewards composure over conscience. In family-court settings, studies by Moss and Singh (2020) and Logan and Walker (2018) found that “professional perpetrators use polish and restraint as a kind of camouflage, while survivors’ exhaustion or emotion are misread as instability.”

What the court reads as credibility, I recognize as performance.

The Psychology of Obsession

When someone devotes this much energy to dismantling another person’s life, it tells you everything you need to know about their psychology.

Studies on coercive control and the “Dark Triad” of personality traits (Paulhus & Williams, 2002) show that when narcissistic and Machiavellian tendencies intersect, manipulation and exploitation often follow, charm without empathy, control without conscience. And while financial control can occur across genders, data from the National Network to End Domestic Violence (2023) show that about four out of five identified perpetrators are men. Yet the behavior itself is not born of gender but of psychology, a pathology of domination, the drive to possess, to dictate, to bend another’s reality to your will.

And when that pathology is carried into post-separation life, it evolves into something even more insidious, an obsession that cloaks itself in procedure and reason.

Those who weaponize systems in this way tend to reveal the same core traits:

Control is their oxygen. Every motion, every spreadsheet, every accusation serves one purpose: to reassert dominance.

They need opposition to exist. Without resistance, they collapse. The conflict sustains them.

They mistake persecution for purpose. Conflict becomes their identity, the only way they feel alive.

They’re addicted to the theater of superiority. Each document is a performance of moral authority.

There is no normal energy in this. This is not logic. It’s compulsion, pathology disguised as order.

But even pathology rarely exists in isolation. Control thrives in company.

In trauma psychology, the network that surrounds such individuals is often called “flying monkeys”, the enablers who protect their illusion of goodness. They are the mother who turns a blind eye to her son’s mistreatment of his former wife and the mother of his children. The live-in partner whose own children benefit from a lifestyle funded by another single parent’s depletion. The friends and colleagues who nod, who stay silent, who choose comfort over truth.

Dr. Evan Stark (2007) described coercive control as “the colonization of a partner’s everyday life.” But for colonization to succeed, it requires settlers, people willing to benefit from what was taken.

Silence doesn’t just permit inequity; it sustains it.

The Reckoning

We’ve been divorced for five years now. Five years since I walked away believing freedom meant the end of control. Five years in which he has been gifted not one, but two brand-new homes, a luxury most people never see in a lifetime. A secure job. A life so comfortable it should have quieted any need to keep fighting.

And yet the filings, the letters, the bills, they keep coming. The energy it takes to maintain this conflict could power a small city.

What does that say about this type of person? And what does it say about us, and about a system that keeps rewarding the performance of composure while punishing the person who tells the truth?

Now, what was once impossible to prove, the quiet, psychological erosion behind closed doors...now is undeniably visible. Walk into the house. Have the coffee. Sit on the new furniture. Look around. And then decide.

This is what covert control looks like when it’s dragged into daylight: luxury built on someone else’s depletion, civility masking cruelty, fairness distorted by privilege. And if we can see that, if it’s right there in front of us, and we still look away, then the question is no longer What kind of person does this? It’s What kind of community allows it to go on?

Because this isn’t melodrama from the movies. It’s the quiet injustice of real life, still happening, five years later. And every time we excuse it, another survivor learns what I did: no one is coming to save us. So we better save ourselves.

I OBJECT

Disclaimer

This essay reflects the author’s personal experience and perspective, informed by publicly available research on financial control and systemic inequity in family-court processes. It is intended to raise awareness of broader institutional and social issues, not to make or imply allegations against any individual.

References & Suggested Reading

McCormack, M. (2025). Endless Litigation in Family Court as a Method of Post-Separation Coercive Control. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law.

Little, G. (2025). They Didn’t Listen: Coercive Control, Alienation, and Systems Misuse in Post-Separation Co-Parenting. University of Newcastle.

Chan, C. (2025). Court-Sanctioned Violence: Self-Represented Victim-Survivors of Family Violence in Ontario Family Law Courts. RepresentingYourself Canada.

Stark, E. (2007). Coercive Control: How Men Entrap Women in Personal Life. Oxford University Press.

Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The Dark Triad of Personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(6), 556–563.

Adams, A. E. et al. (2023). Patterns of Economic Control and Gender Dynamics in Intimate Partner Relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence.

Campbell, A., & Manning, A. (2019). The Role of Bystanders and Enablers in Narcissistic Control Dynamics. Journal of Family Psychology, 33(4), 523–539.

Green, L. (2021). The Silent Chorus: Enablers of Intimate Partner Control in Professional Networks. Violence Against Women, 27(9), 1068–1084.

NNEDV (2024). Financial Control Factsheet. National Network to End Domestic Violence.

Comments